Designing an end-to-end encrypted note sharing service 🔐📝

August 15, 2022

I have used Obsidian for my personal knowledge management (PKM) for over a year now. I love it thanks to its simplicity (everything is stored on disk as plain Markdown files) and the way it promotes connecting my knowledge through links.

However, that last part is also a big pain point for me. There is no trivial way for me to share my knowledge, apart from sending the plain Markdown file; my knowledge base turns into its own walled garden. For example, I take most of my study notes in Obsidian, which works great for me, but is annoying for my classmates when I have to send them plain .md files of my notes.

Other Obsidian users have felt this pain, too. For example, Tim Rogers created the Share as Gist plugin, and a plugin for sharing to Notion has been created as well. In my opinion, none of these solutions is very user-friendly because they require accounts with third-party services, fiddling with API tokens, and offer no end-to-end encryption.

That’s why I decided to build Noteshare.space, my own, end-to-end secured implementation of a “share a note to the web” service. The security mechanism was inspired by Thomas Konrad’s talk about how the (now retired) Firefox Send file sharing service worked.

In this article:

Functional requirements

Now that the stage has been set, let’s review the formal requirements for this project:

- One-click sharing from the Obsidian UI (as easy as sharing a google doc via URL)

- End-to-end encryption (so you can safely share for example work documentation, or a love letter)

- Temporary storage (Noteshare is not intended as a syncing, backup, or permanent hosting solution)

- Shared notes can be opened by non-Obsidian users (i.e. we will build a web viewer)

As we will see, it is quite straightforward to meet all of these. Now, let’s look at the architecture I arrived at.

Architecture

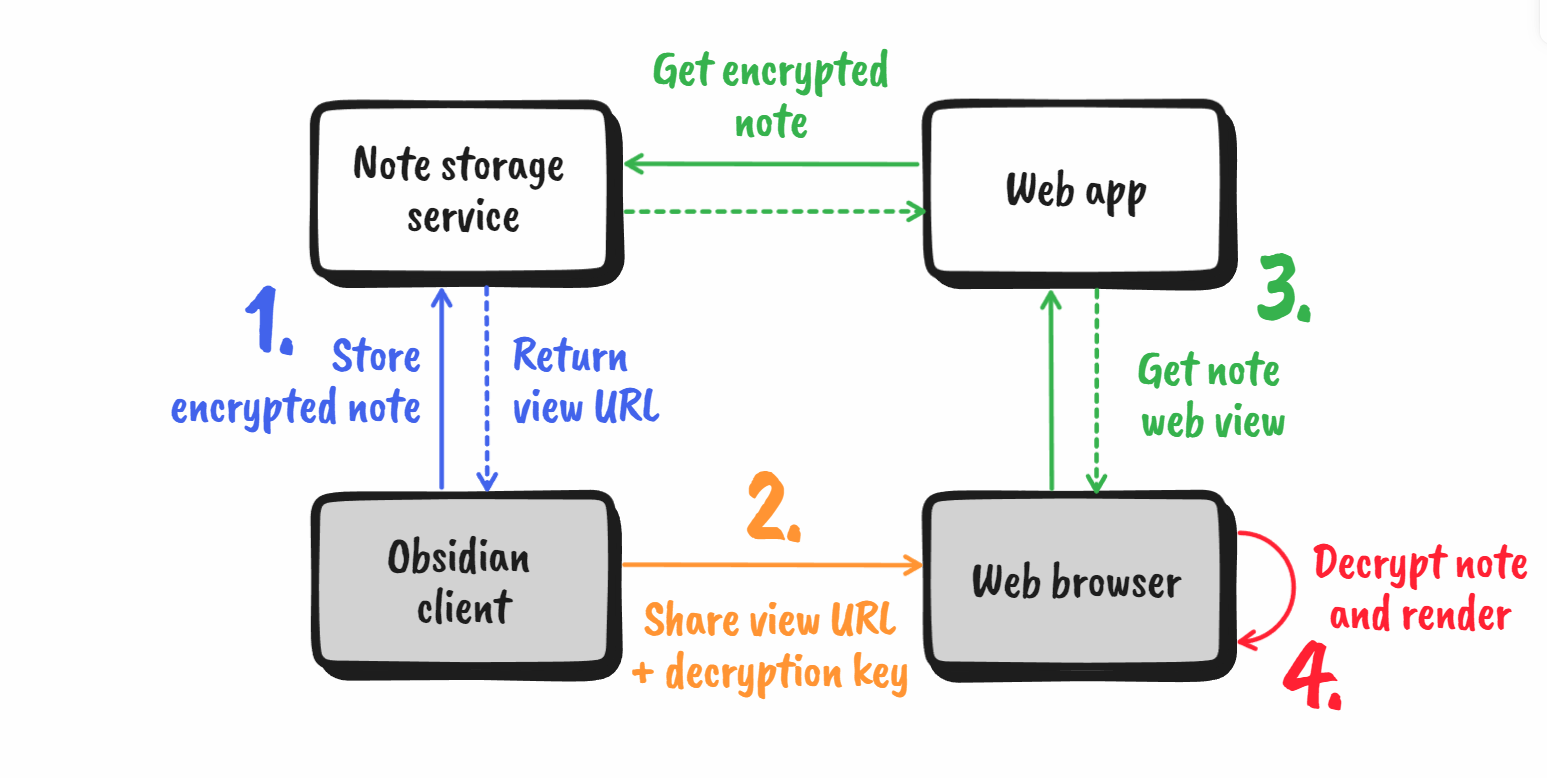

The architecture consists of four components: (i) an Obsidian plugin for encrypting the notes, (ii) a note storage service, (iii) a web application for rendering the web viewer, and (iv) the web browser for opening the shared notes and decrypting them.

The flow for storing and retrieving notes is as follows:

- The user wants to create a share link in the Obsidian application. The plugin encrypts the note with a single-use key (we will see later how we obtain such a key) and sends the encrypted data to the storage service. The storage service then returns the URL where the note can be retrieved.

- The user shares the note URL + decryption key needed to download the encrypted data and decipher the plain text Markdown.

- On opening the URL in a web browser, the web application retrieves the ciphertext and embeds it in a web page.

- The web browser decrypts the ciphertext with the decryption key and renders the Markdown to HTML.

Pretty straightforward, right? Next, we look at how we can implement a secure encryption mechanism for this architecture.

Security mechanisms

Information security is notoriously difficult to get right. That is why you should always stick to well-researched encryption algorithms and security schemes. For this project, I used the AES standard for symmetric encryption with a keyed message authentication code (MAC) to validate the authenticity of the ciphertext.

AES-CBC encryption

Let’s take a look at the encryption first. The following snippet shows the encryption steps as pseudocode:

function encrypt(plaintext, key) {

// 1. Encrypt the message in CBC mode

const ciphertext = AES_encrypt(plaintext, key, { mode: 'CBC' });

// 2. Compute keyed message digest

const hmac = HMAC_SHA_256(ciphertext, key);

return ciphertext, hmac;

}The first step encrypts the plaintext Markdown with the AES algorithm and a 256-bit key. We run the algorithm in conjunction with cipher block chaining (CBC) to encrypt files of arbitrary length. A downside of CBC is that the encryption cannot be parallelized, and is therefore relatively slow. Other encryption schemes, such as Galois/Counter mode (GCM) are considerably faster. However, they usually come with subtle pitfalls; when used incorrectly, it becomes trivial for attackers to decrypt the ciphertext. Regardless, using CBC is not an issue since our file size is in the order of kilobytes.

Keyed message digest

In the second step, we compute a keyed hash (HMAC) of the obtained ciphertext. This way, even if an attacker modifies the ciphertext, it is impossible to compute a new corresponding HMAC without knowing the symmetric encryption key. Using the symmetric key, the recipient of the encrypted note (i.e. the web browser) can verify that the ciphertext was not tampered with before they attempt to decrypt it. The user can now safely send the ciphertext and HMAC values to the storage server without the server being able to read the content of the Markdown.

Generating single-use keys

There remains one small problem: what should we use as the symmetric key? It is absolutely not safe to use Math.random() for this; standard random number generators are only pseudorandom and can easily be exploited to derive the secret key used by the client.

To generate a secure key, we need a cryptographically secure random number generator. In my implementation, I used the PBKDF2 hashing algorithm, commonly used for hashing passwords. Here, we use the Markdown content as the seed ‘password’. This is secure as long as the attacker does not know the Markdown content, in which case there is no point in cracking the key in the first place. To ensure the key is unique even when the same note is shared twice, I concatenate the current timestamp to the seed.

function generateKey(seed) {

// Note: No salt is added because the generated key is for one-time use anyways.

return PBKDF2(seed, (salt = ''), { key_bits: 256 });

}

// Putting it all together

const key_256 = generateKey(time.now() + plaintext);

const ciphertext,

hmac = encrypt(plaintext, key_256);Alternative solution with public/private keys

A remaining issue is that the shared symmetric key can be reused by malicious recipients to change the ciphertext and compute a valid HMAC. This can then be injected into the download traffic of other users without being detected during decryption.

As a solution, we can generate a public-private keypair (e.g. a 2048-bit RSA keypair), use the private key to obtain the ciphertext, and the public key to compute the HMAC. The private key is subsequently thrown away. Recipients can use the public key to verify the message digest and decrypt the ciphertext but a new ciphertext cannot be generated without the private key.

While this is a neat solution, this solves a problem that is beyond the goal for Noteshare, which is to securely exchange text. Therefore I used the symmetric encryption approach. If you want to implement this, make sure you verify that the scheme is secure! Always use verified assymetric encryption schemes such as RSA-OAEP. You might also want to adapt it so that only a symmetric key is encrypted with the private key, since assymetric decryption is orders of magnitude slower than symmetric.

Sharing encryption keys

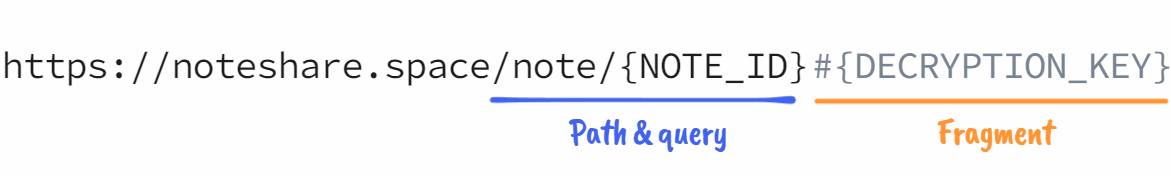

How can we share the decryption key with the recipient when the storage service is not allowed to see it? For this, we can make clever use of the # symbol in URIs:

The ["#" fragment] syntax is most commonly used in web URLs to indicate to the browser to scroll to a specific section of the page (for example: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uniform_Resource_Identifier#Syntax).

What is unique about the fragment component of URIs is that web browsers never include it in their HTTP requests to the server.

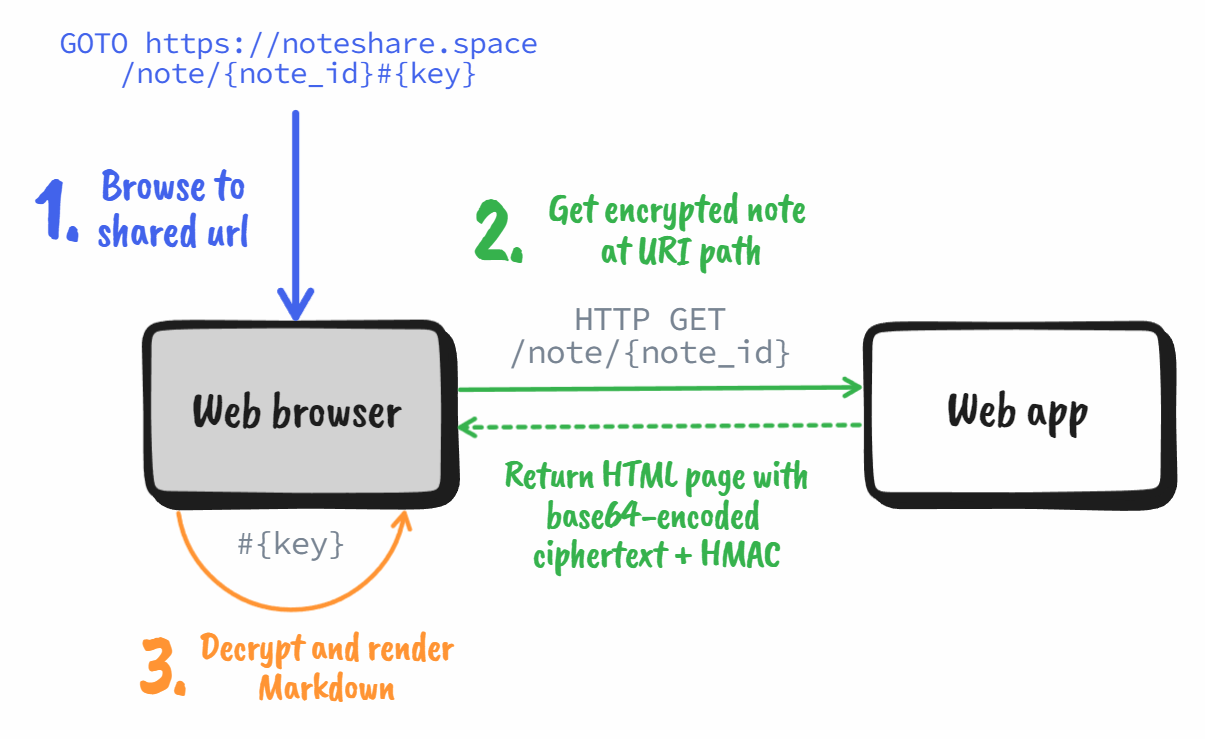

In other words, we can use it to add data to URLs that are accessible to the browser, but not the server. Perfect for our decryption key! The sketch below illustrates the steps the browser takes to render the decrypted note:

We can access the URL fragment using the JavaScript Location API:

/* In the browser: */

// Retrieve ciphertext, hmac and key

const { ciphertext, hmac_received } = getCiphertextFromPage();

const key = location.hash.slice(1); // must slice out the '#' character

// Check if ciphertext is correct

const hmac_computed = HMAC_SHA_256(ciphertext, key);

if (hmac_computed != hmac_received) throw new Error('HMAC check failed!');

// Decrypt

const plaintext = AES_decrypt(ciphertext, key, { mode: 'CBC' });

renderMarkdown(plaintext);And that’s all there is to it!

Conclusion

In this article, I established the groundwork for building an end-to-end encrypted data storage service. It is on this foundation that I built my own encrypted note-sharing service. I initially created it for personal use, but have since opened access to the entire Obsidian community. You can find more information about the service and installation instructions for the Obsidian plugin on Noteshare.space.

Note that this is far from everything you need to host a web service! You must protect your service from abuse in volume of data (rate/volume limiting) and volume of requests (DOS protection). Furthermore, you might want to implement a mechanism to block known bad actors from your system.

I hope you learned something! Feel free to share your thoughts with me on Discord (Maximio#6460) or below.