How to avoid a climate disaster (Gates, 2021)

December 28, 2021

Author: Bill Gates

Words: 81,328

Listening: 8h 49m

ISBN: 978-0385546133

One of the goals for this blog is to force me to think more deeply about the books I read by formulating the main ideas and discussions I want to remember. These posts act as a reference, a book review, and a recommendation.

Recently, I read How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, a book about the solutions we need to avoid, well, a climate disaster. Reading this book offered me a great perspective on climate change and the technologies we need to avert the worst outcome. In this post, I will share with you some of those insights.

Why should I read this book?

With this book, Bill Gates wants to make the general public more informed on what it will take to avoid catastrophic climate change. He addresses the concerns in each industry, lays out the technologies available today, and highlights the areas where major innovation is still required. It is not an overly technical book, readable by anyone with a basic scientific understanding.

If you are intimidated by climate change or are skeptical about whether we can avoid human extinction, this book is for you. The book offers a bird’s-eye view of the problems we need to tackle. And it will give you a practical framework for gauging how well society is progressing towards carbon-neutrality. And if you are like me, you will even have a more hopeful outlook on climate change after reading this.

Main takeaways

To keep this post from getting too long, I will refrain from describing the challenges and innovations in each specific sector. Instead, I will focus on the big picture takeaways. I highly recommend reading the book if you are interested in learning how to decarbonize energy, transportation, manufacturing, etc.

51 Billion to Zero

According to Gates, there are two important numbers to remember about climate change: 51 billion and zero. 51 Billion is the tons of CO2 we emit yearly, today. Zero is where we need to get by 2050 to slow down or halt global warming. Some caveats: (i) Some gases (such as nitrous oxides and methane) are much more potent greenhouse gases than carbon dioxide. The 51 billion refers to the sum of all CO2-equivalent weights, scaled by a gas’s warming potency. (ii) Getting to zero means net zero. Industries such as steel and concrete production or ocean cargo transport are extremely difficult to decarbonize. Thus, to realistically get to zero emissions, we must also look into carbon capture technologies.

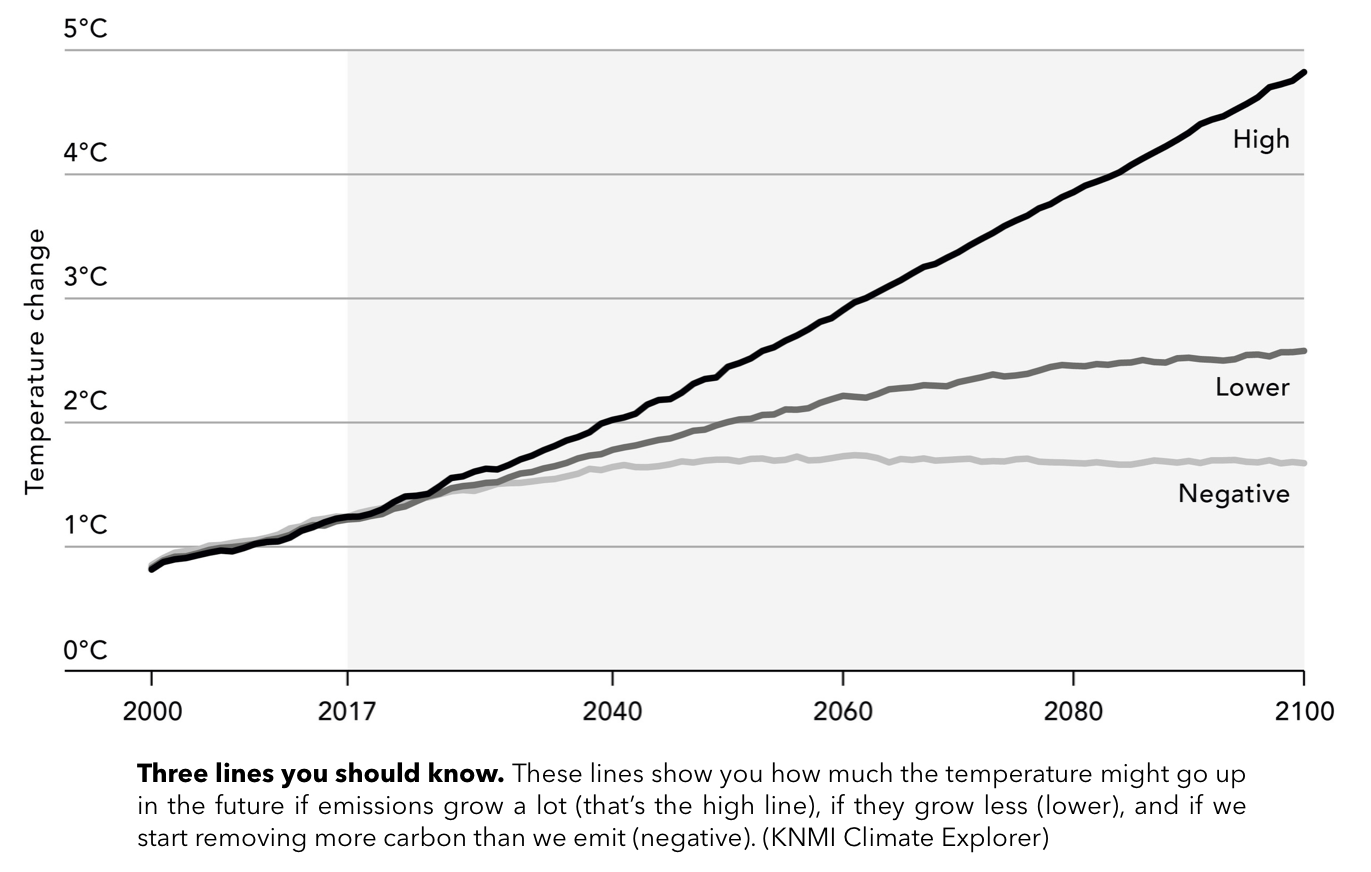

I think this chart from the book best describes the situation we are in and why getting to net zero (or even net negative) emissions is non-negotionable:

To keep the planet livable for humans, we must combine mitigation (avoiding further warming by eliminating greenhouse gas emissions) and adapatation (minimize negative impact of changes that are already occuring). This book is primarily about mitigation techniques, although there is a chapter about adaptation as well.

Decarbonization Is Hard

Fossil fuels are everywhere— so much so that it’s become difficult to notice in how many ways they touch our lives: the electric grid, transportation, plastics, steel, the global supply chain, etc. On top of that, fossils are incredibly low-cost. Oil is cheaper by the gallon than soft drinks!

The following table gives an overview of where most greenhouse gas emissions come from:

| Source | % |

|---|---|

| Production (cement, steel, plastics, …) | 31% |

| Electricity | 27% |

| Crops and livestock | 19% |

| Transportation (people and goods) | 16% |

| Heating and cooling | 7% |

Unfortunately, the price of fossil fuels does not reflect the external costs of environmental damages caused by extraction, refinement, and combustion. That means there is little economic incentive to stop using fossil fuels.

On top of that, some industrial processes are very hard or even impossible to decarbonize. For example, producing cement involves a chemical reaction that releases carbon dioxide, a process for which there is no known alternative. Container ships run on bunker fuel, a dirt-cheap waste product of oil-refining, which makes the global supply chain so cost-effective.

A Plan for Zero Emissions

According to the book, there are four elements to decarbonizing economies: (i) electrify our energy needs where possible; (ii) Generate electric energy using zero-carbon energy sources; (iii) develop alternative fuels for applications where electrification isn’t feasible (think about container ships); (iv) capture the unavoidable emissions (think cement).

Let’s look at each a little more closely.

Electrify everything. The most progress in clean energy is in electric power. It makes sense then to convert as much fossil fuel consumption to clean electric power. That includes electrifying transportation with electric vehicles and replacing gas-powered heaters with electric heat pumps.

Decarbonize the power grid. This one’s simple. We need to generate electricity using zero-carbon sources such as solar, wind, and hydro, instead of coal, gas, or oil. The downside: as we increase our reliance on renewables, the intermittent availability of these sources becomes a bigger problem. This is called the curse of intermittency. Nighttime intermittency for solar can be solved using batteries and is realistically solvable with today’s technology. However, solving seasonal intermittency with batteries is unfeasible. (Think of it like this: holding on to 5 cents of energy in a $100 battery only to charge and discharge once a year makes for a really poor investment) A solution could be to rely on nuclear power as a carbon-free and non-intermittent energy source (according to Gates, it is the only solution to the intermittency problem).

Use alternative fuels. As mentioned before, it is impossible to decarbonize some applications because it is too impractical (think container ships). For this, Gates proposes using alternative fuels that act as a drop-in replacement for fossil fuels. Two candidates discussed in the book are advanced biofuels and electrofuels— although both will require substantial R&D funding to become economically viable.

Capture the remaining emissions. Some emissions cannot be avoided (think cement). To achieve net zero emissions, we will need to capture the greenhouse gases emitted by such processes. There are two categories of carbon capture technologies that can help: point capture and direct air capture (DAC). An advantage of DAC is that it can be powered by surplus generation from renewables.

Green Premiums

One way to measure the progress of zero-carbon alternatives is to track the price of their Green Premium. The Premium amounts to the extra costs when choosing a zero-carbon solution over a conventional fossil-fuel-powered alternative.

Ultimately, it is the Green Premium that determines the adoption rate of a zero-carbon technology, so Green Premiums must decrease over time. This is achieved via technological innovation and optimization, although government policy can also play a role by introducing carbon taxes on dirty energy sources.

Comparing the Green Premium across all industries can help us decide which zero-carbon technologies are the most promising to continue investing in (those with the fastest declining premiums) and which industries require accelerated innovation (those where the Premiums are still too high).

Finally, tracking the Green Premium of zero-carbon technologies is also important to determine whether the available carbon-free alternatives can become affordable enough for middle-income countries.

Zero-carbon and Equality

Energy is a key factor in economic prosperity. It would be incredibly hypocritical and immoral to expect the world to consume less energy to meet zero-carbon goals, as this effectively halts the economic development of developing countries.

As we move towards the future, developing countries must continue to raise themselves from poverty and establish themselves on the world stage. Along with this, their energy demands will rise. Their governments will have to decide: do we build cheap coal power plants to quickly and cheaply meet our demands? Or do we follow the advice of wealthy nations and go for zero-carbon sources?

If we expect developing nations to take the latter choice, clean energy must be dirt cheap. If the Green Premium of making the carbon-free choice is near-zero (or negative!), ideological or scientific arguments will not even play a role in the decision-making. Going zero-carbon will simply be the economically sensible thing to do.

To reach this economic viability, the Green Premiums on zero-carbon alternatives still have a long way to go. Because of this, Gates argues that it is precisely the world’s wealthiest countries that should reach zero emissions first. They possess both the means and the know-how to innovate and bring the Premiums down. There is also an economic incentive: whoever invents the most cost-effective, scalable climate solutions will reap the benefits of an enormous global market.

Thoughts

In this book, Gates provides a very down-to-earth narrative to climate science. I have always seen climate change as something with many intricately interconnected parts, too many for one person to get a real grasp of. But after reading this book, I have a much better idea of where technology must head, and I can judge how well my government is moving in that direction.